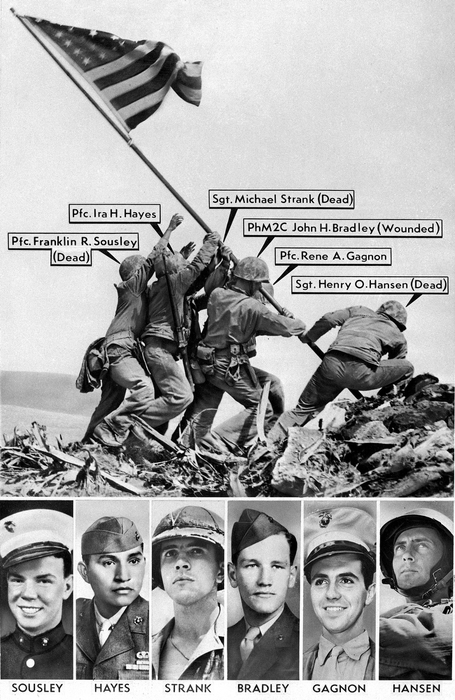

The men who raised the flag over Iwo Jima.

Each year I am hired to go to Washington, DC, with the eighth grade class from Clinton, WI, where I grew up, to videotape their trip. I greatly enjoy visiting our nation’s capitol, and each year I take some special memories back with me. This fall’s trip was especially memorable.

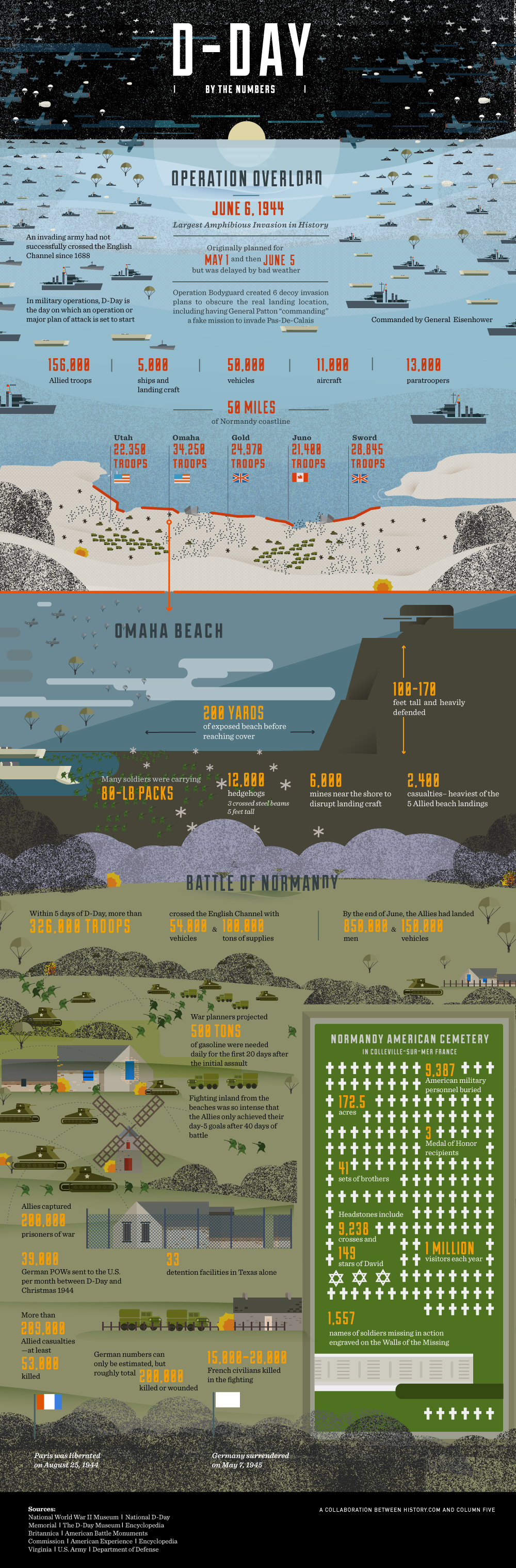

On the last night of our trip, we stopped at the Iwo Jima Memorial. This memorial is the largest bronze statue in the world and depicts one of the most famous photographs in history — that of the six brave soldiers raising the American Flag at the top of a rocky hill on the island of Iwo Jima, Japan, during WW II.

Over one hundred students and chaperones piled off the buses and headed towards the memorial. I noticed a solitary figure at the base of the statue, and as I got closer he asked, “Where are you guys from?”

I told him that we were from Wisconsin. “Hey, I’m a cheesehead, too! Come gather around, cheeseheads, and I will tell you a story.”

(James Bradley just happened to be in Washington, DC, to speak at the memorial the following day. He was there that night to say good night to his dad, who has since passed away. He was just about to leave when he saw the buses pull up. I videotaped him as he spoke to us, and received his permission to share what he said from my videotape. It is one thing to tour the incredible monuments filled with history in Washington, D.C., but it is quite another to get the kind of insight we received that night.)

When all had gathered around, he reverently began to speak. (Here are his words that night.)

“My name is James Bradley and I’m from Antigo, Wisconsin. My dad is on that statue and I just wrote a book called “Flags of Our Fathers” which is #5 on the New York Times Best Seller list right now. It is the story of the six boys you see behind me.”

“Six boys raised the flag. The first guy putting the pole in the ground is Harlon Block. Harlon was an all-state football player. He enlisted in the Marine Corps with all the senior members of his football team. They were off to play another type of game. A game called ‘War’. But it didn’t turn out to be a game. Harlon, at the age of 21, died with his intestines in his hands. I don’t say that to gross you out, I say that because there are generals who stand in front of this statue and talk about the glory of war.”

“You guys need to know that most of the boys in Iwo Jima were 17, 18, and 19 years old.”

(He pointed to the statue) “You see this next guy? That’s Rene Gagnon from New Hampshire. If you took Rene’s helmet off at the moment this photo was taken and looked in the webbing of that helmet, you would find a photograph of his girlfriend. Rene put that in there for protection because he was scared. He was 18 years old. Boys won the battle of Iwo Jima… Boys… Not old men.”

“The next guy here, the third guy in this tableau, was Sergeant Mike Strank. Mike is my hero. He was the hero of all these guys. They called him the “old man” because he was so old. He was already 24. When Mike would motivate his boys in training camp, he didn’t say, ‘Let’s go kill some Japanese’ or ‘Let’s die for our country.’ He knew he was talking to little boys. Instead he would say, ‘You do what I say, and I’ll get you home to your mothers.'”

“The last guy on this side of the statue is Ira Hayes, a Pima Indian from Arizona. Ira Hayes walked off Iwo Jima. He went into the White House with my dad. President Truman told him, ‘You’re a hero…’ He told reporters, ‘How can I feel like a hero when 250 of my buddies hit the island with me and only 27 of us walked off alive?’ So you take your class at school, 250 of you spending a year together having fun, doing everything together. Then all 250 of you hit the beach, but only 27 of your classmates walk off alive. That was Ira Hayes. He had images of horror in his mind. Ira Hayes died dead drunk, face down at the age of 32… ten years after this picture was taken.”

“The next guy, going around the statue, is Franklin Sousley from Hilltop, Kentucky. A fun lovin’ hillbilly boy. His best friend, who is now 70, told me, ‘Yeah, you know, we took two cows up on the porch of the Hilltop General Store. Then we strung wire across the stairs so the cows couldn’t get down. Then we fed them Epsom salts. Those cows crapped all night.'”

“Yes, he was a fun lovin’ hillbilly boy. Franklin died on Iwo Jima at the age of 19. When the telegram came to tell his mother that he was dead, it went to the Hilltop General Store. A barefoot boy ran that telegram up to his mother’s farm. The neighbors could hear her scream all night and into the morning. The neighbors lived a quarter of a mile away.”

“The next guy, as we continue to go around the statue, is my dad, John Bradley from Antigo, Wisconsin, where I was raised. My dad lived until 1994, but he would never give interviews. When Walter Cronkite’s producers or the New York Times would call, we were trained as little kids to say, ‘No, I’m sorry, sir, my dad’s not here. He is in Canada fishing. No, there is no phone there, sir. No, we don’t know when he is coming back.’ My dad never fished or even went to Canada. Usually, he was sitting there right at the table eating his Campbell’s soup. But we had to tell the press that he was out fishing. He didn’t want to talk to the press.”

“You see, my dad didn’t see himself as a hero. Everyone thinks these guys are heroes, ’cause they are in a photo and a monument. My dad knew better. He was a medic. John Bradley from Wisconsin was a caregiver. In Iwo Jima he probably held over 200 boys as they died. And when boys died in Iwo Jima, they writhed and screamed in pain.”

“When I was a little boy, my third grade teacher told me that my dad was a hero. When I went home and told my dad that, he looked at me and said, ‘I want you always to remember that the heroes of Iwo Jima are the guys who did not come back… Did NOT come back.'”

“So that’s the story about six nice young boys. Three died on Iwo Jima, and three came back as national heroes. Overall, 7,000 boys died on Iwo Jima in the worst battle in the history of the Marine Corps. My voice is giving out, so I will end here. Thank you for your time.”

Suddenly, the monument wasn’t just a big old piece of metal with a flag sticking out of the top. It came to life before our eyes with the heartfelt words of a son who did indeed have a father who was a hero. Maybe not a hero for the reasons most people would believe, but a hero nonetheless.

Michael T. Powers

©Copyright 2000 by Michael T. Powers