World War I was a brutal and bloody conflict that claimed millions of lives and left countless scars on the survivors. The soldiers who fought in the trenches faced unimaginable horrors: constant shelling, poison gas, disease, hunger, and rats.

But amid the darkness and despair, there was a glimmer of hope and comfort: cats. These furry friends served as loyal companions, brave hunters, and even life-saving detectors. In this article, we’ll explore how cats became the heroes and mascots of WWI.

Cats as Rodent Hunters

One of the biggest problems in the trenches was the infestation of rats and mice. These rodents fed on the corpses and food supplies, spread infections, and gnawed on the equipment and wires. They also tormented the soldiers with their squeaking and biting.

To combat this menace, the military deployed an estimated 500,000 cats to the front lines. These cats were trained or adopted by the soldiers, who provided them with food, water, and shelter. The cats, in turn, hunted down the rodents and kept them at bay.

The cats were so effective that they were sometimes rewarded with medals or promotions. For example, a black cat named Pepper was promoted to corporal by the Canadian troops for his outstanding service. Another cat, named Tom, received the Blue Cross medal for killing 300 rats in a single week.

Cats as Gas Detectors

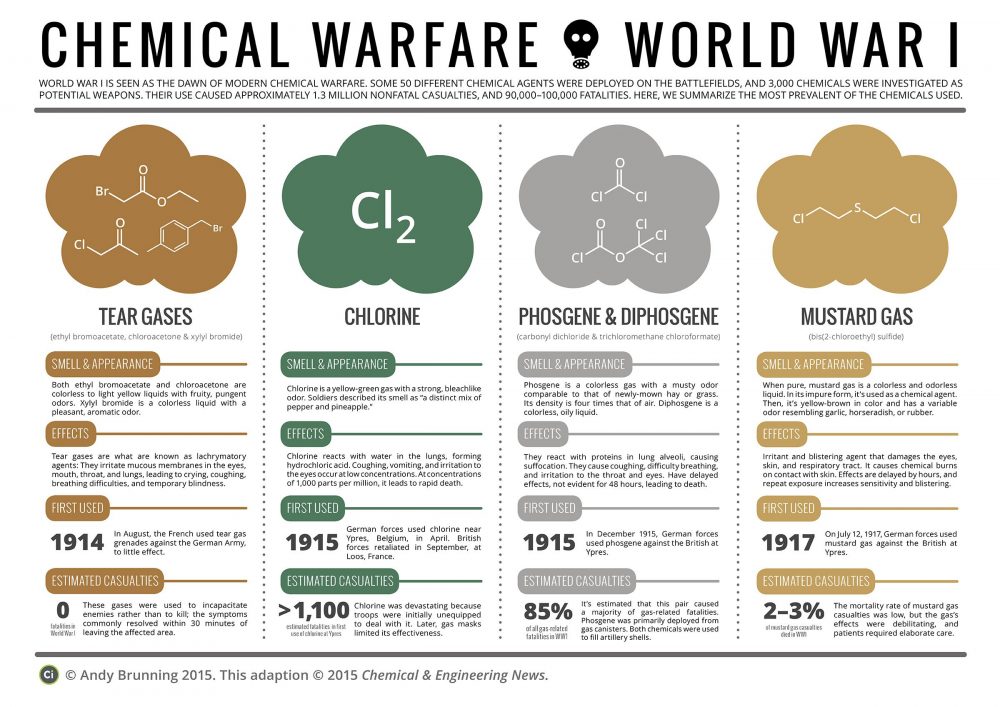

Another danger that the soldiers faced was the use of chemical weapons, such as chlorine and mustard gas. These gases could cause severe damage to the lungs, eyes, and skin, and often resulted in death. The soldiers had to wear gas masks to protect themselves, but they were not always available or reliable.

That’s where the cats came in handy. Cats have a more sensitive respiratory system than humans, and they can detect the presence of gas before it becomes lethal. The soldiers would watch the cats for signs of distress, such as coughing, sneezing, or running away. If they saw the cats reacting, they would quickly put on their masks or seek cover.

Some cats even saved their owners’ lives by alerting them to gas attacks. One such cat was Pitouchi, who belonged to a Belgian soldier named Lieutenant Lekeux. Pitouchi was born in the trenches and stayed with Lekeux throughout the war. One day, Lekeux was hiding in a shell hole, sketching the enemy’s positions, when a German patrol spotted him. Pitouchi, who was scared by the noise, jumped out of the hole and drew the Germans’ attention. They fired two shots at him, but missed. Pitouchi then jumped back into the hole with Lekeux, who realized that the Germans had mistaken him for a rat. The Germans laughed and moved on, leaving Lekeux and Pitouchi unharmed.

Cats as Mascots and Pets

Beyond their practical roles, cats also served as symbols of hope and joy for the soldiers. The cats offered the soldiers a sense of companionship and normalcy in the midst of chaos and violence. The soldiers would pet, play, and cuddle with the cats, and share their rations and stories with them. The cats helped the soldiers cope with the stress and loneliness of war.

Many cats became the mascots of their units, and were given names, collars, and uniforms. Some cats even traveled across the battlefields with their owners, riding on their shoulders, helmets, or backpacks. The cats boosted the morale and spirit of the troops, and were often featured in photographs, letters, and newspapers.

Some cats also served as messengers of peace and friendship between the warring sides. During the famous Christmas Truce of 1914, when the soldiers from both sides exchanged greetings and gifts, some of them also tied messages around the cats’ collars and sent them across the no man’s land. The messages expressed their hopes for an end to the war and a better future.

Conclusion

Cats were more than just animals in WWI. They were heroes, friends, and allies. They helped the soldiers survive and endure the hardships of war, and they also brought them happiness and warmth. Cats were the perfect companions in the trenches of WWI.