American History: Sarah Malinda Pritchard

Sarah Malinda Pritchard, perhaps the most famous female soldier from North Carolina, served alongside her husband in the Confederate army, and later assisted the Union military. Born in 1839, she married William McKesson Blalock at the age of seventeen, and settled on a farm near the base of Grandfather Mountain. William, who went by the nickname “Keith,” remained loyal to the Union at the outbreak of the war, and refused to enlist the Confederate army. However, in March 1862, faced with new conscription laws requiring all men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five to serve in the army, Keith Blalock and his wife, disguised as “Sam” Blalock and claiming to be Keith’s younger brother, enlisted in Company F, 26th North Carolina Infantry.

Six days prior to the Blalock’s enlistment, the 26th North Carolina had fought in the Battle of New Bern, and the regiment was recovering near Kinston. “Sam” gave her age on enlistment as twenty, but was described in later accounts as a “good looking sixteen-year-old boy” weighing “about 130 pounds, height five feet four inches.” It was noted that for the next month Sam , tenting and eating with Keith, did all the “duties of a soldier,” and was “very adept at learning the manual and the drill.”

Sarah Malinda’s Confederate service was quite short-lived, however. Keith, ever anxious to find a way out of the army, approached the regimental surgeon, Thomas J. Boykin, with a complaint of a “rupture” (hernia) and “poison from sumac.” The injury may have been a preexisting condition however it is thought that he rolled around in sumac in order to gain the rash. Initially the surgeons thought he was suffering from smallpox due to the severity of the disorder. On April 20, 1862, Keith was discharged from Confederate service for “disability.” That same afternoon, “Sam” came clean to the regimental commanders, including Colonel Zebulon Vance, and immediately was discharged from service.

After their release, the Blalocks made their way back to their mountain home. Precisely what happened to them in 1863-1864 is unclear. One account states that Keith was subsequently wounded in the arm as the couple were pursued into the wilderness atop Grandfather Mountain by Confederate conscription and enrolling officers attempting to force Keith to rejoin the army. If he had been properly discharged, however, and had papers proving that, they could not have legally reenlisted him. In his later years, Keith asserted that he had never been properly discharged. Tradition also states that he helped Union escapees from Salisbury prison cross the mountains into Tennessee.

At some point in the fall of 1863 or spring of 1864, Keith made his way across the mountains into eastern Tennessee, where on June 1, 1864 he enlisted at Strawberry Plains in Company D, 10th Michigan Cavalry. The company records indicate that at least four other eastern Tennessee or western North Carolina Unionists joined the same company. He later claimed in his Union army pension that he spent the majority of his time in service as a scout. He acknowledged two injuries in his pension that do not appear in his service records: a gunshot to the arm while operating in Caldwell County in the summer of 1864, and a second wound, which cost him his left eye, on January 15, 1865.

Historians as well as fiction writers have made numerous claims that Sarah Malinda Blalock took part in many of Keith’s scouting forays. One story involves Malinda being wounded in the shoulder in an early 1864 attack on the home of Carroll Moore, the father of a former friend and comrade of the Blalocks. She indeed may have helped him, but one must account for the fact that she had a one-year-old child at the time that needed care, and Keith does not mention her presence alongside him in any of his pension correspondence postwar.

After the war, Keith Blalock murdered a man who was responsible for the killing of his stepfather during the conflict. He managed to escape prosecution. For a brief time the family moved to Texas, but eventually returned to North Carolina, settling as farmers in Mitchell County (in an area that is present-day Avery County). Malinda died in 1903, and is buried in the Montezuma Community Cemetery alongside Keith, who was killed in 1913 in an accident on the railroad.

Sarah Malinda Blalock’s month-long enlistment in the Confederate army, and her later assistance to the Union military, made her unique among North Carolina’s women veterans.

American History: The Confederate Guerrilla

The James brothers were Confederate guerrillas in Missouri during the Civil War.

Jesse James, one of the most violent outlaws of the wild west, got his first taste for violence as a Confederate guerrilla during the Civil War.

Although he came to be known as one of the most dangerous bandits of the west, James started out his life as a religious, peaceful farm boy who seemed destined for a career as a minister, like his father Robert, who died in California while preaching to gold miners.

Those plans changed when the Civil War broke out in 1861 and brought chaos to his sleepy hometown of Kearney, Missouri.

As slave owners with six slaves working on the family hemp farm, the James family sympathized with the Confederate cause.

Born in 1847, Jesse was too young to join the army and begrudgingly stayed behind as he watched his older brother Frank leave home and join a group of Confederate guerrillas known as Quantrill’s Raiders, run by outlaw William Quantrill.

The war soon came home to Jesse when his brother’s activities in the gang led the Union army to the James farm.

Looking for information on Frank’s whereabouts, the soldiers beat Jesse and tortured his stepfather.

Historians believe this violent experience is what pushed Jesse to join his brother and the gang, at just 16 years old, in the spring of 1864.

Led by “Bloody Bill” Anderson, the gang was made up mostly of wealthy, slave owning families seeking to protect Missouri from the anti-slavery Union ideals. They terrorized anyone who sympathized with or supported the Union army in Missouri.

During a raid in the summer of 1864, Jesse was shot in the chest but recovered in time to take part in one of the bloodiest atrocities of the Civil War: The Centralia Massacre.

Described by witnesses as a “carnival of blood,” the Centralia Massacre was a raid on the small Missouri town of Centralia.

While the gang was looting the town and murdering anyone who protested, a train pulled into the center of town with 21 unarmed Union soldiers on leave from the army.

Anderson and his men quickly stripped the soldiers of their clothing, so they could use them as disguises, and shot them dead.

Nearby Union troops caught wind of the violence and headed toward the town to put an end to it. The gang set up an ambush, captured and then killed all 150 soldiers. Jesse himself was credited with killing Union major A.V. E. Johnson in the massacre.

Many of the soldiers were beheaded, disemboweled and slowly tortured. After the violence was over, the gang then proceeded to mutilate and scalp the bodies.

Anderson died a few weeks later after he was killed by members of the Missouri State Militia and most of the gang returned to quiet civilian life after the Civil War ended, except for Jesse and his brother.

Still angry over the defeat of the Confederate army, the brothers vowed to continue fighting.

The James brothers began robbing banks, including a bank owned by the man they believed killed Anderson, and murdered him on the spot.

When the press mentioned Jesse by name it gave him a thrill and spurred him to continue.

Jesse acquired his own gang and together they robbed banks, trains and stagecoaches while declaring themselves heroic Southern fighters:

“We are not thieves,” he wrote in a letter to a newspaper, “we are bold robbers. I am proud of the name, for Alexander the Great was a bold robber, and Julius Caesar, and Napoleon Bonaparte.”

James and his men eventually ran into trouble after a robbery in Minnesota in the summer of 1876 turned deadly and two members of the gang were killed.

The James brothers went into hiding but Jesse eventually became restless and started another gang. Jesse met his end when two men in his group, Robert and Charley Ford, decided to kill Jesse hoping to collect the reward Governor Crittenden had placed on Jesse’s head.

Robert Ford shot and killed Jesse James on April 3, 1882 by shooting him in the head when his back was turned. The Ford brothers later stood trial for murder but were pardoned by the governor.

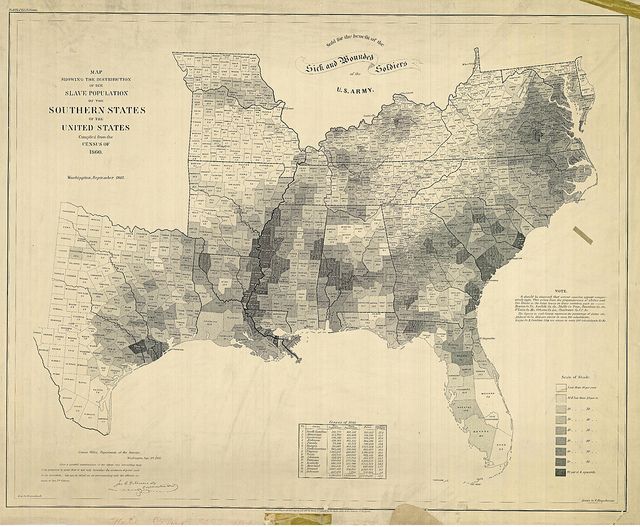

American History: A Map Of American Slavery

A Map of American Slavery

One of the most important maps of the Civil War was also one of the most visually striking: the United States Coast Survey’s map of the slaveholding states, which clearly illustrates the varying concentrations of slaves across the South. Abraham Lincoln loved the map and consulted it often; it even appears in a famous 1864 painting of the president and his cabinet.