Are you looking for something to do? Well here you go.

f you can crack the code above, congratulations — you’re the first person to do so. And you may be helping solve a murder case in the process.

On June 30, 1999, a 41-year-old man named Ricky McCormick was found dead in a field about 15 to 20 miles northwest of St. Louis, Missouri. McCormick was unmarried but had at least four children. He was unemployed on and off for years. He had previously been convicted of statutory rape but was out on parole. He had chronic lung and heart problems and, five days prior to his death, was in a hospital in St. Louis getting a checkup. (He left the same day.) At the time of his death, he had multiple home addresses in the area.

The FBI investigated his death and found virtually no answers. McCormick’s body was badly decomposed (the FBI identified his body via his fingerprints), preventing authorities from determining the cause of death. McCormick’s whereabouts for the days between that doctor’s visit and the discovery of his body were, and remain, unknown. How he got to this field is also unknown, as McCormick didn’t know how to drive and public transportation did not service the area. There were no known people who would have the motive to kill him, nor any signs of suicide.

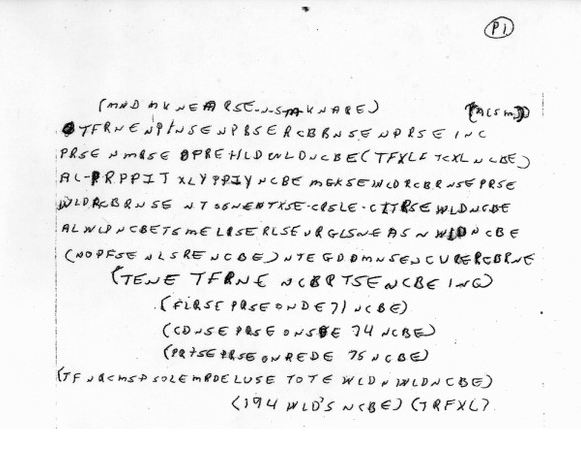

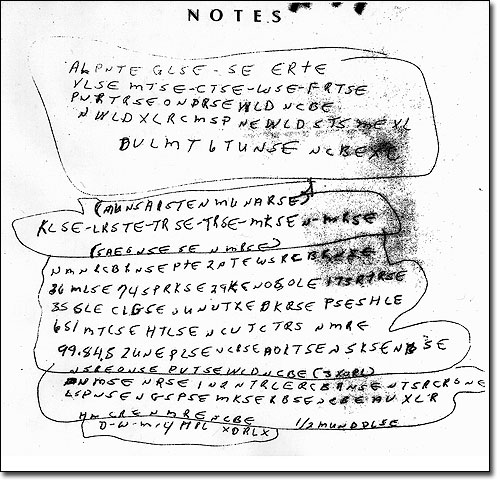

But while there were few answers, there were some clues. Two, in fact. In McCormick’s pockets were two notes, one above and another seen below.

In March of 2011 — more than a decade after McCormick’s death — the FBI disclosed that these potential clues existed. The Bureau’s reason for not disclosing this sooner isn’t known, but its reasons for doing so then are. The FBI was stumped, and wanted help. They set up a webpage, here – still active, as of this writing — asking the world to assist in deciphering the messages. Despite the “outpouring of responses” to the call to action (the FBI had to set up a separate page solely for the gathering of theories), the code remains encrypted.There is, of course, the chance that McCormick (or whomever wrote the note) simply put gibberish to paper.

Have any ideas? You can let the FBI know via this link, but don’t expect to be showered in money if you do — there’s no reward being offered.

Bonus fact: The CIA has an uncracked-code mystery of its own. As reported by Wired, in 1988, the Agency commissioned the creation of a sculpture named “Kryptos” which contains four encrypted messages. Three of them were solved (here are the solutions) after its dedication in 1990, but the fourth one remains unsolved to this day. The creator of the sculpture, an artist named James Sanborn, asserts that there is, indeed, a real message hidden within, and has given a clue or two to its meaning.