The U.S. Government Poisoned Alcohol During Prohibition and 10,000 people were killed.

In desperation to make effective the floundering Prohibition on alcohol, the U.S. government — unable to convince the public consumption of booze constituted a moral transgression — intentionally poisoned the supply in a last-ditch attempt to enforce State-mandated sobriety.

This “Chemist’s war of Prohibition” became, as the outspoken opponent and New York City chief medical examiner in the 1920s, Charles Norris, hauntingly described, “our national experiment in extermination.”

Rather than keep people away from bathtub gin and the constant flow of liquor in hidden speakeasies — the State-sanctioned toxic experiment killed thousands of people who simply wanted to imbibe.

Hospitals accustomed to treating illnesses caused by bad batches of homemade alcohol — bootleg supplies not infrequently were tainted with metals and other contaminants — were not prepared for a spate of deaths in New York City over the Christmas holidays in 1926. This wasn’t, they realized, a typical case of toxic back-alley booze — in a mere two days, 23 people lost their lives.

People began dropping like flies, in fact, and a list of similar incidents quickly lengthened.

Thirty-three people perished in just three days in Manhattan in 1928 from tainted hooch believed to be wood alcohol — and by that time, the public felt federal intervention might be necessary. However, as TIME reported shortly afterward.

“Everyone expected the intervention and assistance of Federal forces, lately so loudly active in Manhattan. But no one expected what actually happened. The Federals announced that the government could do absolutely nothing. The statement of the Federal Grand Jury read as follows: ‘Inasmuch as wood alcohol is not a beverage, but a recognized poison (analogous to prussic acid or iodine) and its use and sale are not regulated by any of the Federal laws, we respectfully report that in those particular instances the subject matter is for the consideration of the State authorities rather than the Federal authorities. The State laws regulate the sale of poisons and provide for punishment for their improper use and sale.’”

By the time of the repeal of Prohibition in the December 5, 1933, ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment, estimates surmise no less than 10,000 had perished as a direct result of the government’s horrendously ill-fated poisoning program. As Slate’s Deborah Blum reported,

“Frustrated that people continued to consume so much alcohol even after it was banned, federal officials had decided to try a different kind of enforcement. They ordered the poisoning of industrial alcohols manufactured in the United States, products regularly stolen by bootleggers and resold as drinkable spirits. The idea was to scare people into giving up illicit drinking. Instead, by the time Prohibition ended in 1933, the federal poisoning program, by some estimates, had killed at least 10,000 people.”

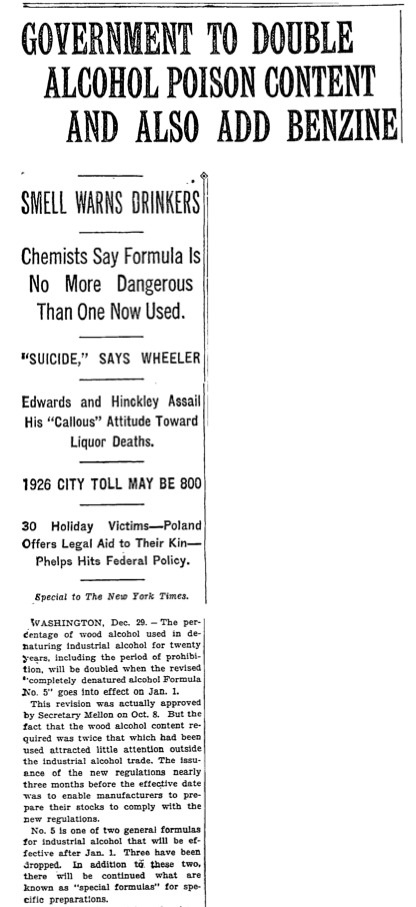

In order to poison the supply, the government had to turn to the base ingredient commonly used by bootleg manufacturers, as TIME Magazine explained,

“For years, that industrial alcohol had been ‘denatured’ by adding toxic or unappetizing chemicals to it — the idea was originally so that people couldn’t escape beverage taxes by drinking commercial-use alcohol instead — but it was still possible to re-purify the liquid so that it could be consumed.

“So, as TIME reported in the Jan. 10, 1927, issue, a solution emerged from the anti-drinking forces in the government: that year, a new formula for denaturing industrial-grade alcohol was introduced, doubling how poisonous the product became. The new formula included ‘4 parts methanol (wood alcohol), 2.25 parts pyridine bases, 0.5 parts benzene to 100 parts ethyl alcohol’ and, as TIME noted, ‘Three ordinary drinks of this may cause blindness.’ (In case you didn’t guess, ‘blind drink’ isn’t just a figure of speech.)”

Prohibition had widespread support, and although not everyone agreed with the government’s new method of coercion meant to quash the nation’s obvious love affair with alcohol — TIME noted New Jersey Senator Edward I. Edwards called it “legalized murder” — those who did pontificated on the supposed amorality of drinking as justification for poisoning deaths.

“The Government is under no obligation to furnish the people with alcohol that is drinkable when the Constitution prohibits it,” asserted poisoning and Prohibition advocate, Wayne B. Wheeler. “The person who drinks this industrial alcohol is a deliberate suicide … To root out a bad habit costs many lives and long years of effort. …”

The Chicago Tribune strikingly editorialized in 1927, as cited by Slate,

“Normally, no American government would engage in such business. … It is only in the curious fanaticism of Prohibition that any means, however barbarous, are considered justified.”

Myriad ruinous government programs, in particular, prohibitions on alcohol and cannabis, have been implemented under the premise of protecting the people from some misbegotten ill — but, in practice, these efforts too often play out more disastrously than if the State had never intervened in the first place.

Ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1919 meant a ban on the sale, manufacture, and transport of alcoholic beverages — and the subsequent passage of the Volstead Act provided the rules for enforcement of Prohibition when it went into effect in 1920.

Anti-alcohol organizations constantly sermonized on the evils of drinking, and though the notion seems almost quaint in 2017, the post-war atmosphere in the U.S. welcomed any movement to prevent further degradation of morals — or, more accurately, the morals of a specific group of people whose grandstanding centered around alcohol.

Unsurprisingly, vocal support for the platform overrepresented the reality — the business of banned booze immediately and decisively boomed. Blum wrote,

“Alcoholism rates soared during the 1920s; insurance companies charted the increase at more than 300 more percent. Speakeasies promptly opened for business. By the decade’s end, some 30,000 existed in New York City alone. Street gangs grew into bootlegging empires built on smuggling, stealing, and manufacturing illegal alcohol. The country’s defiant response to the new laws shocked those who sincerely (and naively) believed that the amendment would usher in a new era of upright behavior.”

None of that shock nor the high-and-mighty stance from which the temperance movement preached moral uprightness ever targeted the government for recklessly condemning random alcohol drinkers to death.

When the State takes the reins of any flippantly righteous high horse, it’s a veritable guarantee the program is doomed to failure — and Prohibition was no exception.

Indiscriminately killing more than 10,000 people by deliberate poisoning, however, belies the less candid goal the government would never admit: control at any cost.

Congress and the White House doubled the amount of methanol in industrial liquor and added benzine to the mix. The poisonous substances were meant to discourage people from drinking bootleg products. (New York Times)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.