If you try and read the “words” in the title above from left to right, you’ll realize right away that you can’t — the first few characters aren’t even letters. Try it from right to left and it’s not much better. But read it upside down, and you’re likely in business. It says “upside down but looking normal,” and it describes the experiences of a man named George M. Stratton.

Maybe.

Stratton was born in 1865 in Oakland, California. By his early thirties, he was a professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, but he took interest in psychology. He switched disciplines, became the school’s first chair of its psychology department, and founded the school’s first experimental psychology lab (and one of the first in the nation at that). And for one of his experiments, he found a very willing test subject — himself.

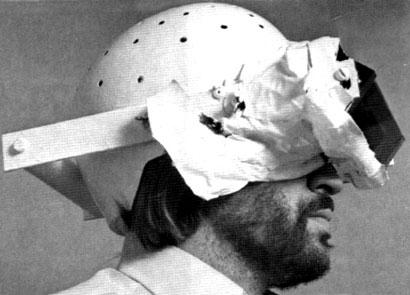

It started with something that looked like a crude version of this:

Those are a modern version of something called “inverting glasses” which, as the name suggests, makes the world appear upside down. About 120 years ago, Stratton fashioned a pair for himself, wore them for about 21 and a half hours straight, and recorded his findings. What he learned (pdf) was that trying to navigate the world while looking at it flipped on its head isn’t very fun — you feel nauseous and disoriented throughout. The good news was that when he took the glasses off, he felt much better nearly immediately. The bad news (beyond the nausea etc., that is), was that his brain couldn’t compensate for the changes in visual inputs.Undaunted, Stratton tried the experiment again — but this time, wore the inverting glasses (or went blindfolded, to sleep) for eight days straight. And this time, Stratton reported, his brain flipped the world back into position. Wikipedia summarizes:

By day four, the images seen through the instrument were still upside down. However, on day five, images appeared upright until he concentrated on them; then they became inverted again. By having to concentrate on his vision to turn it upside down again, especially when he knew images were hitting his retinas in the opposite orientation as normal, Stratton deduced his brain had reprocessed his vision and adapted to the changes in vision.

Amazing — but not necessarily completely true. Stratton’s experiment didn’t meet more modern standards for such things; for example, his test group was very small (one person) and included someone (himself) with a vested interest in a certain outcome. The small sample size plus the inherent risk of bias gave future generations reason enough to try to replicate Stratton’s findings, and they haven’t been able to, at least not entirely. As io9 reported, in one relatively recent study (1999), test subjects donned inverting glasses for a six to ten day time period. The world didn’t turn upside down for them — so that part of Stratton’s findings haven’t been replicated.

However, our brains do compensate to a large degree. The subjects “reported feeling as though they had been turned upside down in the regular world. Essentially, even though they knew it wasn’t true, they felt like they were walking on the ceiling or the sky.” So while it’s unclear what Stratton saw and experienced, it’s likely that he was able to navigate the upside down world after a while. Just like the title of this article, if you look at something upside down for long enough, it begins to make sense.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.